** This is Part TWO of the 2022 Best Ball Tournament Strategy Guide: For Part ONE please check that out HERE. **

When I was young, my father told me a story about seeing Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back for the first time. He had waited in line and was only able to see the second earliest showing. As he was readying to go in, someone from the first showing walked out of the theatre yelling “VADER IS LUKE’s FATHER!!”

Madness ensured, with a line full of angry fans apoplectic their long-awaited sequel was ruined by such a cruel act. The reality is that sequels are often disappointing. Don’t believe me? Watch Mean Girls 2. Knowing this, I’ve experienced a degree of anxiety in putting together Part II of my best ball strategy guide after the first part – not entirely unlike George Lucas’ debut Space Opera – was enjoyed by tens of degenerates living in basements across North America.

Nevertheless, I’ve summoned the courage, fortitude and galaxy brain to bring you another excavation of the most minute edges of the hardest to win fantasy football contest on the planet.

Let father stretch my hands and deliver you Pt. 2 of the Best Ball Tournament Strategy Guide.

A Quick Recap

If you want the full brunt of my thoughts on Underdog’s Best Ball Tournaments, Part 1 is the place to start. It covers the format, the incentive structure, and the archetypes of players to target in detail. Just hammer that link below.

Underdog Best Ball Strategy: The Guide to Drafting in 2022 – Part 1

If you’ve read that piece but want a quick refresher, here is the quick and dirty version.

Best Ball Mania – and the associated Puppy Tournaments – are extremely difficult to win. You need a combination of elite player selection and good fortune to even advance to the final week never mind win it. However, the payout structure dictates you need to be shooting for a high finish in the final week to make it a profitable enterprise. Therefore, we need to be making every draft decision with the ceiling we need and the format of the tournament in mind.

This led to a discussion of the different types of ‘wide band’ archetypes and factors of players I am targeting in drafts. As well, I discussed the way ownership intertwines with your win equity similar to a DFS tournament. Also, I went over how drafting wide band players can help maximize lineups with a mix of low-owned options and elite-season long performers come the final week.

The theme of maximizing ceiling outcomes and unique lineups in the final week will be pervasive for the remainder of this article as well. For more on these DFS-style strategies and how they apply to best ball check out my series from 2021 on just that.

The Strategic Levers of Best Ball Tournaments

In Part 1 I identified five core strategic levers in best ball tournaments, which were as follows.

- Player Selection

- Cost of Acquisition

- Exposure

- Lineup Construction

- Correlation

In that piece, we primarily focused on player selection. This week’s focus will be on Cost of Acquisition and Exposure – though each element is ultimately filled with interchangeable concepts.

Cost of Acquisition

You may be wondering why I phrased ‘draft price’ in such an ornate fashion. Am I an obnoxious prick? Or do I have a point? Well, I’ll answer the later and leave the former for you to decide.

When people talk about cost in fantasy, they’re usually talking about ADP. And more specifically, they’re discussing whether they are “in” or “out” at cost. Expanding further, what this really means to most folks is whether they think it likely a player finishes the season higher or lower than his draft cost.

For Example: Should we draft Brandin Cooks at WR26? For most folks, that decision comes down to whether you think Cooks will finish higher or lower than WR26. This is a notion often referred to, in short hand, as “beating his ADP.”

Personally, I think this an example of generating flawed answers to ill-considered questions. As I stated in the succeeding tweet, I am vehemently opposed to making decisions in this fashion.

“Beating ADP” isn’t a thing.

You are playing against people not ADP. Your draft picks are the array of weapons at your disposal to generate the outcome you need.

You don’t choose your weapons in a vacuum. You choose them based on your opponent and the game environment.

— Jakob Sanderson (@JakobSanderson) July 5, 2022

Beating ADP is a Parallel Game

The conflation between “beating ADP” and cost consciousness is perfectly illustrated in the replies to the above tweet. Most folks interpreted my tweet as saying I don’t care about ADP when drafting. In actuality this could not be further from the truth. I very much care about ADP when drafting. Rather, it was a criticism of how we define successful results, and especially, how we define the goals of each pick.

‘Beating ADP’ is a binary outcome. Either you are better than your drafted position or worse. Thus, the way we project for binary outcomes is with the use of median: at the 50th percentile of a player’s range, will he surpass his ADP in season-long rank? While we likely don’t think about it in such analytical terms, that’s what we often do when deciding to click the draft button.

As I mentioned last week with regard to advance rate, beating ADP is a parallel game lacking inherent validation of our strategy for winning a tournament. Our brain wants to conflate these easily definable measures of ‘success’ to grade our abilities because the reality is more abstract and less satisfying.

We are drafting a range of outcomes, not a median. In a six-figure field, the range we are optimizing for is not the one most likely to happen. Therefore, we cannot use median outcome to project good picks at cost any more than we can use end of season result to validate the selection. Consider fantasy football’s most bimodal asset: Alexander Mattison.

Assessing the Unassessable

The following is an excerpt rom an earlier Thinking About Thinking Column:

In games Dalvin Cook missed, Mattison averaged 22.45 fantasy points per game. In all other games, he surpassed six fantasy points just once.

Mattison’s distribution is largely bimodal. His ranges of outcomes in a given season are an amalgamation of his range with Cook healthy, his range if Cook is injured, and the likelihood of such an injury.

Mattison last year averaged 8.06 fantasy points per game yet rarely scored close to that number. That’s because of his distribution.

How can we possibly use projection to assess the merits of Mattison as a pick? And how absurdly results-oriented would it be to assess the strength of that pick in hindsight based on Cook’s health? The reality is most players have more unpredictable contingencies built into their price than we often want to admit. Therefore, we should probably use the same general approach in assessing their outlook as an amalgamated range we do with Mattison when discussing say, Gabriel Davis vs. Brandin Cooks. We discussed much more on the elements of an ADP to examine in Part 1.

If you want more on this, check out a recent episode of Stealing Bananas in which the veracity of projection-based drafting is challenged.

Price vs. Opportunity Cost

Okay – so we’re now trying to think of each player’s value in terms of ranges rather than medians. But that was mostly covered last article, so what’s new?

I felt it was important to discuss the difference between ‘beating ADP’ in a results-oriented sense vs. a cost sense based on the response to the earlier tweet as a prefatory exercise. When I discuss cost of acquisition, I do not do so in terms of opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of Gabriel Davis, for instance, is typically any other player drafted at pick 46. At receiver, this is usually one of Jerry Jeudy, Allen Robinson, or Brandin Cooks. Whether you wish to pay that is based on your priors regarding player selection, and the construction of your lineup.

In terms of cost of acquisition, I am instead referring to price. Unfortunately, the price is not set by us but rather the market at large. If you want a player, you either have to pay the market price or likely be underweight on that player.

Even for my most aggressive stands, I am highly conscious of price. I want to access the highest ceiling lineups possible. This means it is integral for me to maximize the efficacy of each draft pick. I am also compiling a portfolio of teams. Thus, it is not necessary for me to make consistent, arbitrary reaches past ADP for players I value above the market. With enough drafts, you will find a high exposure of a given player is rather attainable. Simply draft your preferred options at ADP when given an appropriate draft slot. Then take them every time they fall past ADP to an atypical spot in the draft.

In fact, we can demonstrate this with math!

Passive Exposure

The following is an excerpt from my past strategy column comparing Best Ball and DFS tournaments.

Nobody recommends filling out DFS lineups with $1,000 salary left over in the milli-maker because you wanted to ‘get your guys.’ Play whoever you want’ actually means ‘any set of correlated pieces can be viable in a given slate as part of a well-constructed lineup.’

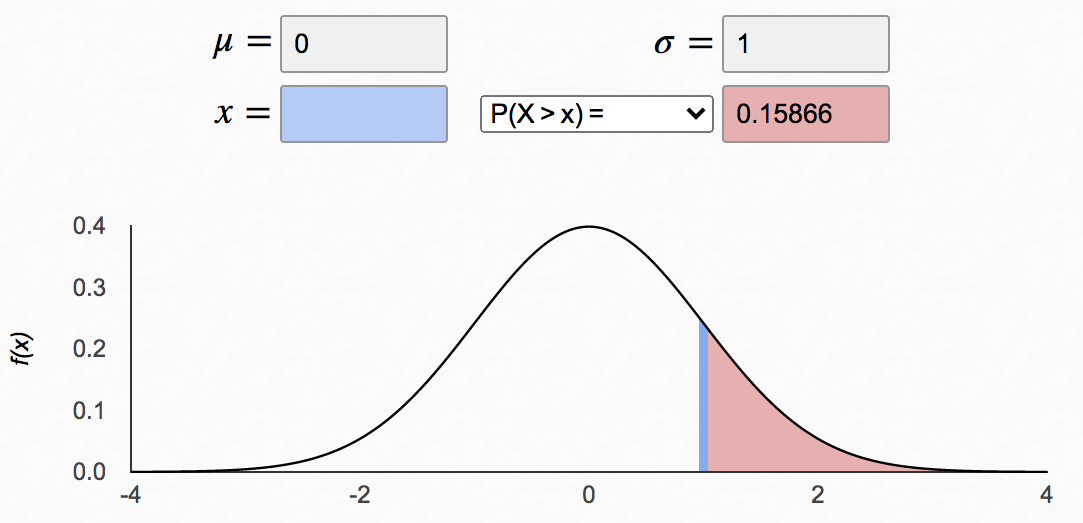

There is a concept in statistics called the ’68-95-99.7′ rule. It states 68-percent of outcomes in a probabilistic sample occur within one standard deviation of the mean in normal distributions. If we assume a player’s draft position is a normal distribution, there is a 32-percent chance an outcome is one standard deviation outside the mean and a 16-percent chance they fall one standard deviation past ADP. The following diagram demonstrates this.

One year later, Hayden Winks put proof to what I had theorized. ADP IS normally distributed. This means that in fact the 68-95-99.7 rule applies, and you can generate significant exposures to preferred targets without reaching ahead of ADP. Winks’ data goes further in describing just how far you can expect players to fall and how often. He essentially calculates the standard deviation of the distribution.

Best Ball ADPs – Is It Okay To Reach?

🔗: https://t.co/x20cKfwFdH pic.twitter.com/V02ImevLUV

— Hayden Winks (@HaydenWinks) May 26, 2022

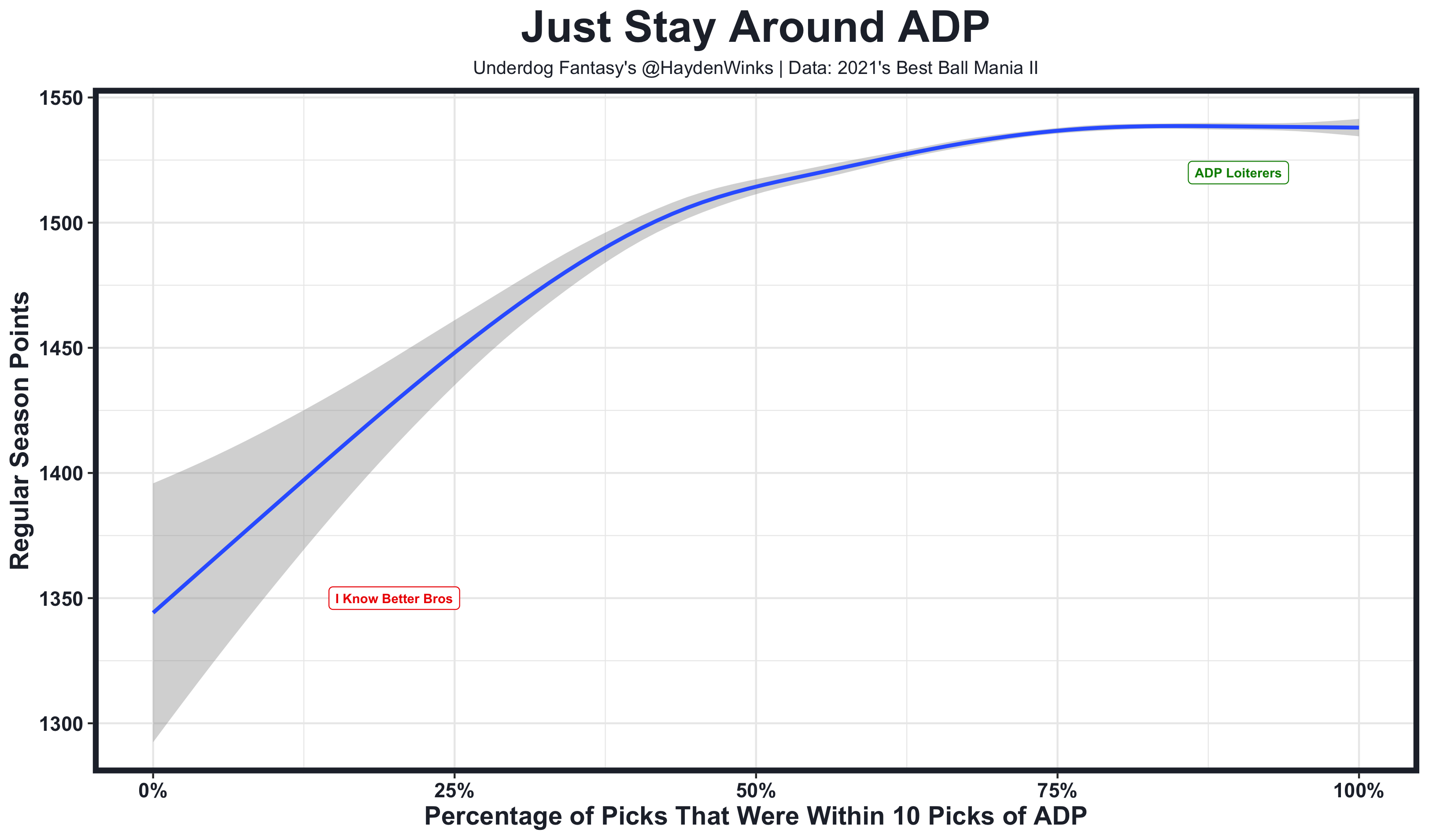

Unsurprisingly, Winks’ data showed that drafters selecting players significantly ahead of ADP fair much worse than those who are cost-conscious.

Drafting Within the Market

Putting this all together, you can’t control the cost of an item. A person can only control the price you are willing to pay. You may think a beer is worth $2.50. However, if you’re at a ball game in 100 degree heat, your choice is likely to pay $10 or huddle by the water fountain. I can’t blame you for shelling out an Alexander Hamilton for a Miller Light in a pinch. But I’m sure you don’t buy beer at the most expensive liquor store on the block when you’re at home.

As emphasized last week, we should be taking an archetypal view of player selection. There are several player whose archetypes I want to draft at an ADP I think is under-priced. But for those I think are over-priced, the only choice I have is to accept the cost or fade them. This group of players is one I am not drafting ahead of ADP. But within correlated stacks and/or when available at or after ADP, I’m willing to blend them into my portfolio. I want to generate exposure to favorable archetypes who carry unpalatable costs in a way that optimizes the benefit of the pay-off. My hope is this can offset my limited exposure overall.

I do not think expensive ADPs should prohibit you from drafting profiles worth targeting. However, you should be limiting exposure to your preferred players to when they’re available at or near their ADP.

Exposure is More than a Percentage in your Spreadsheet

Exposure is the universal unit of preference measurement in best ball. If someone asks you “do you like Javonte Williams?” the common response is to respond with some variation of a dairy product’s fat content. Not a fan? “two-percent.” All in? “33-percent.” Take it or leave it? “10-percent.”

Designating my best ball exposures in terms of dairy product:

• Skim Milk (0%) – Zeke

• 2% Milk – Chubb

• Whole Milk (4%) – Mixon

• Half and Half (10%) – Javonte

• Cooking Cream (15%) – R White

• Cofee Cream (18%) – Barkley

• Whipping Cream (33%) – Hendo

— Jakob Sanderson (@JakobSanderson) July 24, 2022

We need to think about our best ball portfolios as a collection of lineups more than an aggregation of players. The point of playing portfolio best ball is to generate a large number of combinations in hope the aggregate of your stances on players, teams, lineup constructions and correlations produces a winning lineup. While this is inherently a random exercise, we can orchestrate our own chaos.

We should be drafting each player with intentionality as to which lineups they’re a part of. This means striking a balance between placing a player in unique combinations, generating ADP value on that player’s lineups, correlating the player with team-mates or Week 17 opponents, and diversifying the build structure and player combinations around that player within your own portfolio.

The Dangers of Passive Drafting

For example, two of my favorite selections are Saquon Barkley and A.J. Brown. It is quite natural to draft each in round two and three respectively, which means I often draft them together. However, this can create problems which risks damaging a large portion of my portfolio.

- If I am “right” about one of these players but “wrong” about the other, I risk submarining one of my highest leverage stands by consistently pairing them with a dud.

- If I am “right” about both, I’m likely to face several other Brown + Barkley teams in the playoff week since they are so easily drafted together. Even if both are major hits, you’d likely prefer to have a lower-owned partner for each in your lineups in the one-week playoff round.

- What are the tertiary likelihoods of common pairings? If I’m often drafting Barkley with Brown, it means I’m MORE likely to draft Jalen Hurts on Barkley teams, as well as New Orleans Saints stacks and bring backs (the Eagles’ week 17 opponent). Do I want to tie an outsized chunk of my Barkley position to Jameis Winston or Jalen Hurts for no reason related to Barkley himself?

While I spent most of the first half of this article praising the benefits of drafting ‘passively,’ there are drawbacks as well. In the remainder of this article, I will outline how I am choosing to optimize my exposures in an intentional fashion.

The Portfolio’s Dilemma

I like to think of the lineups of each player as a mini-portfolio; especially among my ‘stands.’ In the same fashion I would not want to draft 200 zero-RB teams, or have 100-percent exposure to A.J. Brown. I don’t want each of my Justin Jefferson teams to follow a repeatable pattern. At the same time, I’m entirely aware of just how many combinations are possible, and how few of them we get to build. This creates a dilemma.

If I want to take a strong stand on two players at cost, and draft them together often, there is a risk of one’s failure diminishing my stand on the other. However, there is a likely reality that I could draft both players on every single team, both could be major wins at ADP, and I still don’t have the right combination of players around them to get to in the final week AND win when there.

On one hand, the more compounded our bets become, the fewer outcomes we need to predict in order to win. This is the same theory behind stacking for a season-long correlated benefit. On the other hand, compounding bets brings in heightened risk of spoiling your most successful selections. It also diminishes the uniqueness of your lineups in the playoffs if both bets hit.

Portfolio Reduction: A Middle-Ground

I don’t believe there to be a “solution” to the dilemma posed above. But there are choices we can make to capture the benefits of both sides. My proposed option is portfolio reduction.

This is a four-tiered system by which I’m approaching my player selection and lineup combinations based around archetypal drafting.

The Power of Zero

There has been a lot of discussion as to how high your exposure should be to your most-rostered players. There is less discussion on what percentage of the player pool you are willing to zero-out entirely. That’s what I’m most interested in this year.

IMO the best way to get a favourable balance b/w

– Getting ++Exposure to players you want

– Maximising combinations of players you want

– Maintaining ADP discipline

– Hyper-focusing Game StacksIs to critically analyze each pocket of the draft and choose 2 guys to zero out

— Jakob Sanderson (@JakobSanderson) June 1, 2022

I acknowledge that players I dislike in terms of cost and profile still have a strong chance to post high advance rates or even make a meaningful difference in the playoff weeks; especially in the early rounds. However, it is in those early rounds where it is most difficult to stake out high exposure stands to your preferred players. This is especially true if you are willing to take every player at a given cost.

I acknowledge for instance that Najee Harris could finish as a top five running back and post 25 points in Week 17. However, in my view, his range of outcomes – particularly his ceiling – is lower than comparably priced players such as Stefon Diggs, Travis Kelce, Davante Adams and Dalvin Cook. Unlike those players, Harris plays in a projected below average offense, and he has not demonstrated the ability to create explosive plays. I cannot stake out an at or over-market stance on Adams, Cook, Diggs and Kelce without correspondingly below-market stances to other players drafted around them. In fact, I prefer players drafted later – such as Aaron Jones, Saquon Barkley and Mark Andrews – to Harris straight up.

Passive vs. Active Diversification

So the question becomes; do I “passively diversify” by selecting Harris sparingly when he falls past ADP? Or do I stick to my ranks and take Barkley or Jones in those situations? If I were playing in only 12-person leagues, I would select Harris when he falls past his ADP tier. However, in a tournament setting, in the event I’m wrong on Harris, and he is #TheGuyYouNeed, what are the odds the winning Harris team comes from my two-percent exposure? They are exceedingly low. I would prefer to fully zero players such as Harris who land in my tier four. I prefer to preserve my ‘bullets’ for the players I’m able to more intentionally build a sub-portfolio of teams around.

Reducing my overall portfolio allows for greater diversification within my sub-portfolios. Since I’ve already bet big on Barkley and against Harris, I derive a more realizable benefit from adding another Barkley team with a unique lineup combination than spraying and praying my way through the bottom of my exposure list.

Portfolio Reduction in Action: Actioning the Tiers

The tiers are defined in an intentionally subjective fashion. Ultimately, this is a strategy for how to draft rather than who to draft. The last article covered the elements I’m looking for in player archetypes. The criteria I base my archetypes on are: youth, contingent value, offensive environment, situational ambiguity, and usage or traits which generate explosive plays, or high-value touches. You need not share my inputs, nor do you have to agree on which inputs describe which players to follow this approach to portfolio building.

Once I’ve determined the extent to which a player fits my archetypal criteria, I focus on their projected range of outcomes vs. ADP. More specifically, I weigh that player’s range of outcomes vs. the opportunity cost of alternatives in their pocket of the draft. This two-step process sorts each player largely into the four tiers described earlier.

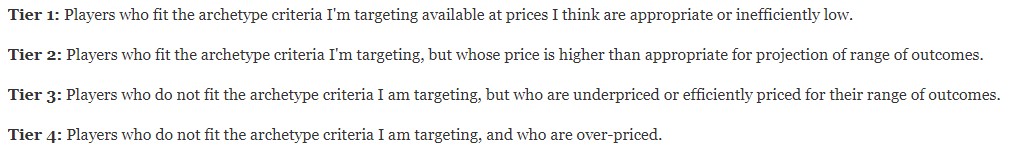

Below is a picture of my tier divisions for the first three rounds to help illustrate the idea.

Note: for the most part, this system is how I approach receivers and running backs. Due to positional scarcity and lineup construction I approach quarterback and tight end differently. Expect much more commentary on those positions next article.

Again: this is MY subjective sorting based on MY subjective criteria. You likely hate my criteria and hate my sorting. And you probably hate me for hating your favorite player. That is fine because you can follow this same portfolio strategy and use entirely different criteria and then sort players however you like. For that reason I will not be turning this 4,000 word article into a 10,000 word article by explaining why I draft more Tee Higgins than Mike Evans.

Building your Sub-Portfolios

The focus of my sub-portfolios are my tier-1 players. These are the players I am making central to my 2022 best ball season. I want to build a host of teams anchored around this group. To maximize each stand, I want to build a portfolio around each which contains a broad array of structures, stacks and player-combinations in addition to correlating the specific players as much as possible.

To do this, I naturally select the combinations of tier two and tier three players which best fit each lineup. In general, I aim for an equal mix of these tiers on each team in order to balance players I expect to have strong season long value (tier 3) with players whose ceilings I want access to despite challenging costs (tier 2). Up until this point, I’ve mostly been drafting the most correlated teams I can at the best prices available and hoping to passively diversify best I can.

As we get closer to the end of draft season, I plan to survey my teams to determine which combinations are most over and under represented with each player. For example, I am taking a strong stance on 49ers and Raiders game stacks this year. I want to make sure I have SF-LVR stacks with almost every member of tier one at all price points. I also want to have a fairly even assortment of tier two and tier three players around each of these stands.

Creating Unique Combinations

Lastly, I want to use my last drafts to build more unique pairings. This will be a major focus of next article, so I will only touch on it here briefly. But the nature of snake drafts are such that certain players will be much more commonly paired together than others. This is exacerbated in early rounds when ADP is adhered to more closely. I’m drafting lots of Davante Adams and Tee Higgins. But how often am I (or anyone) drafting both?

Not too often since they are drafted on opposite turns.

My preference is to generate unique pairings by benefitting from a player who falls well past their ADP rather than reaching ahead of ADP. For that reason, I do not force unique pairings often early in a tournament or draft season. I would rather leave open the possibility of getting lucky in a given draft. Or, I would rather wait for a player’s ADP to change such that new combinations are more possible.

Impossible Teams

However, when a tournament is close to full or near the end of the summer, I will go out of my way to create teams which are impossible to build at ADP. I do so by drafting my “favorite” players well ahead of ADP. When doing so, I try to compound this uniqueness benefit by accessing unique Week 17 game stacks or leveraging off of hypothetical scenarios (injuries, busts or unexpected team situations).

An example: Jalen Hurts is currently drafted at the five-six turn and Derek Carr is drafted at the nine-10 turn. For that reason, I would prefer to draft A.J. Brown ahead of his ADP in early round two than draft Davante Adams in early round one to generate the unique combination. In this scenario, I would also consider drafting players such as Michael Gallup, Chris Evans, Jamaal Williams or A.J. Dillon. These players stand to benefit from the failure of common early round two picks I’m betting on Brown to beat out.

Optimizing Lineups

This is my last point of what’s been a very long article. I’m extremely grateful you’re still reading.

The driving principle behind lineups I’m more likely select my tier two and tier three players in is different for each. When selecting tier two players, my primary question is: if this player hits their ceiling, what’s the most likely lineup to maximize the benefit from that ceiling?

Assuming the Upside Case on Big Swings

For example, the poster boy of tier two is Gabriel Davis. I believe Davis to be over-priced for his talent and projection. However, he also checks off nearly every box of my archetype criteria.

Because of this, when I’m drafting Davis I have to assume he’s hitting the highest end of his range of outcomes to pay off his cost. In particular, I focus on Week 17. As a result, the lineups I select Davis in are especially likely to include Josh Allen or a Bengals stack. As well, I’m less likely to include Davis as part of double stacks than I would be with players whose median projection I think is stronger at cost. I’m essentially betting on my projection to be wrong. So, I want to think of the likeliest ways that can occur. The first scenario on the list is injury or under-performance of Stefon Diggs.

I also prefer players like this to be drafted within a high-volume structure of their position. As discussed last article, part of the benefit of this type of player is the chance of them being low-owned in the final. Therefore, I want to structure my team such that I maximize my chance to ‘drag’ that player into the playoff weeks despite a poor regular season. Because of this, I’ll likely have more Davis in 2-5-9-2 type builds than zeroRB builds where I’m highly dependent on weekly production from my early receivers. I would never want to build exclusively one structure for each player, but I will err more on one side or another depending on the profile.

Maximizing the Utility of Small Wins

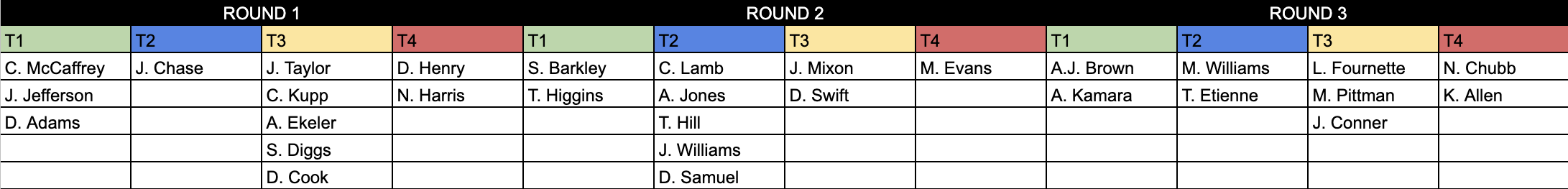

For players in tier three, I take the opposite approach. These are profiles I’m projecting to be ‘small win, small loss’ type players. Therefore, I want to mix them in sparingly to avoid reducing my upside. When I do, I want this archetype to serve a purpose. Jarvis Landry is a great example of this type of player. For his target earning profile, I believe he is underpriced. However, his usage pattern throughout his career begets limited weekly upside. I want to prioritize Landry only on teams with a low total number of receivers. Also, I want to draft Landry when I’ve drafted injured receivers or rookies whom I expect to be of more use at the end of the year than the beginning.

The Final Word

If this feels like a lot of useless galaxy braining… it likely is. The reality is that “picking the best players” is the best way to boost your expected value. But unless you have Biff’s almanac from back to the future, you likely don’t know who that will be. Therefore, controlling how we draft s the best way we can maximize who we draft.