The term ‘cuffing season’ refers to young singles’ tendency to seek romantic partners when the weather turns cold. The single life seems appealing when it’s all beaches and margaritas, but come December; who will roast chestnuts with you on the open fire? I think most agree the logic of this dating motivation is as sound as applying for the bachelor franchise. And yet, in the wake of season-ending injuries to J.K. Dobbins, Travis Etienne and Cam Akers, fantasy managers have been scared into similarly confounding process errors.

It’s time to put a definitive end to the great handcuff debate.

Leading the pro-handcuff side is high-stakes veteran and fantasy radio host Jeff Mans, who argues every single Dobbins team should have been drafting Gus Edwards in the eighth round.

Different year, same argument and @Jeff_Mans is tired of it.

Handcuff your running backs in #FantasyFootball so you don't have to stress when an injury happens.

🎙️🏈🎧⬇️ pic.twitter.com/kIb6rjKk2a

— Fantasy Sports Radio (@SiriusXMFantasy) August 30, 2021

To support his claim, he opts for a summary of his sleeping ability rather than data analysis. Don’t get me wrong; at PlayerProfiler we would never get in the way of your beauty rest. Thus, we will mine the data you need so you’re free to focus on counting sheep.

The Definitive Case Against Handcuffs

Over the course of this article, I will table a four-pronged case against drafting your own handcuff:

1) Drafting your own handcuff decreases your maximum win equity.

2) The structure of a typical fantasy league rewards maximizing ceiling outcomes – not mitigating threats to your floor.

3) There are silent costs to rostering your handcuff.

4) Handcuff running backs often fail to hit value even after an injury.

First let’s establish a definition. When I say ‘handcuffing,’ I am specifically referring to drafting a second running back from the same team as your starting running back. Combinations such as Ronald Jones and Giovani Bernard who come with lower opportunity costs, and co-existing roles, is a different matter. Throwing multiple darts at an ambiguous backfield, such as Tevin Coleman and Ty Johnson is also excluded from this discussion.

At the macro-level, handcuffing involves committing to one player as a pillar for the success of your team, and another who can only maximize their value with your earlier pick failing. It is a conscious decision to sacrifice one of your chances to draft a league winner in order to mitigate risk. Is the safety worth it?

I. Handcuffing Decreases Your Maximum Win Equity

Herm Edwards would never handcuff a running back. Why? Because you play to win the game.

There is only one base heuristic you should use for each pick of your fantasy draft. It is not about who projects for the most points, the safest floor, or increases your peace of mind. It is about which player selection most increases your odds to win the money.

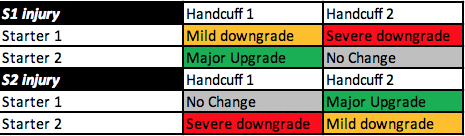

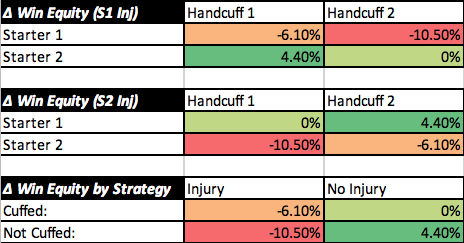

In order to assess this in the context of the handcuff debate, we need to remember you do not have injury omnipotence. The table below illustrates the effect on your team for each combination of starter and handcuff assuming you have the choice to pick one of two equally valued starters and one of two equally valued backups without the benefit of hindsight.

This table spells out the obvious; if your starter gets hurt your team suffers.

While drafting the handcuff can mitigate that, the only way to benefit from a running back injury is by drafting the backups of other players’ lead rushers.

We know this ‘two v. two’ never precisely exists, but I am a believer in starting these conversations at the macro level, before diving into player-specific takes which can distract from the overall theory. A disclaimer; if your case for drafting a handcuff is that a particular running back is more injury prone, or you want to ‘lock up a backfield’ at all costs, these are are flawed arguments. If you’re projecting an injury for a starter, just draft the backup. If you want high exposure to a backfield in general, take both in alternating leagues. This allows you to derive greater benefit on your hedge, without sacrificing your upside.

Let’s get back to the previous table. How can we quantify this?

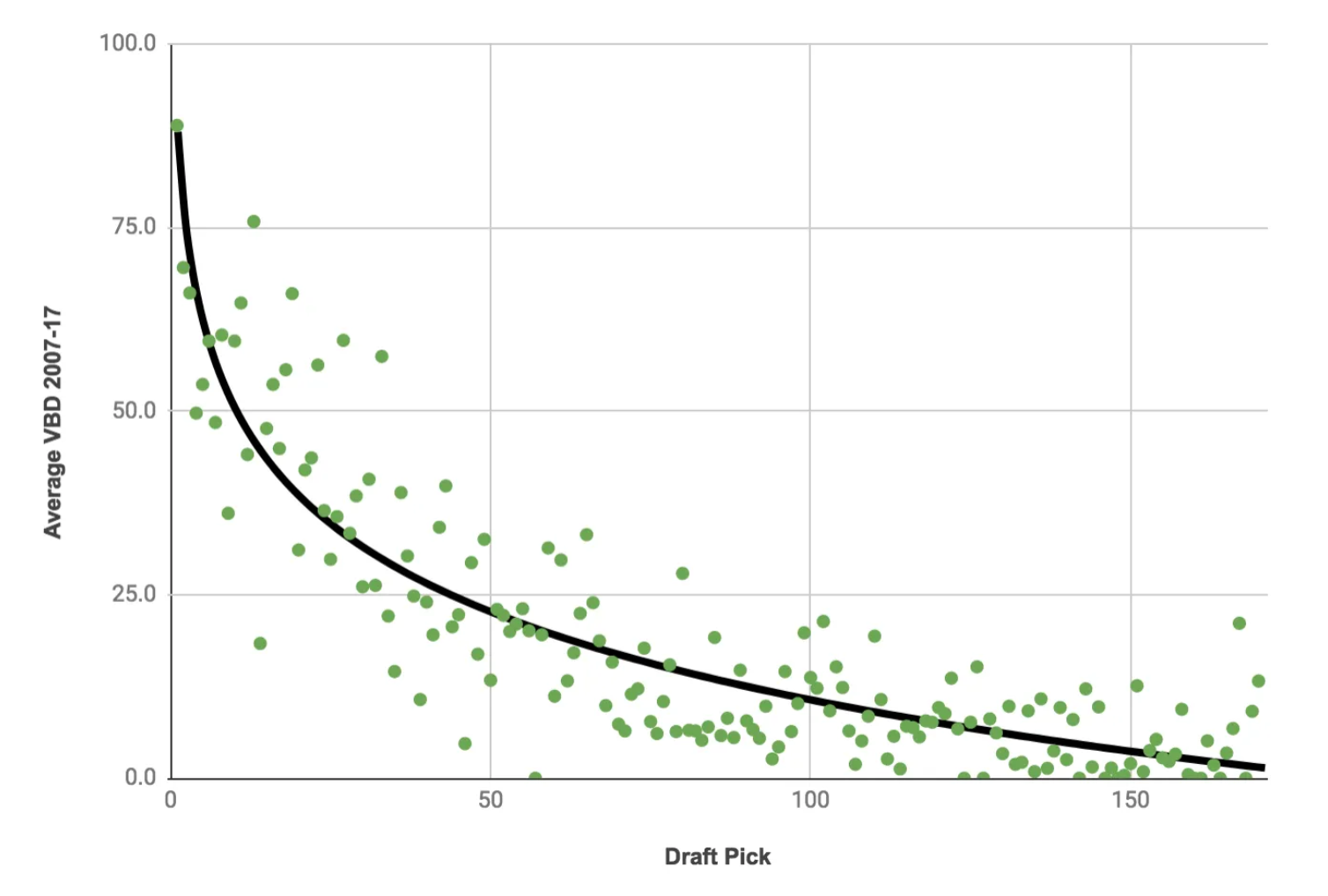

I will be borrowing from the work of Riley McAtee‘s fantasy draft pick value chart.

In a study for The Ringer, McAtee charted the average performance of draft picks at each ADP and assigned an expected value quotient to each. Following from the J.K. Dobbins–Gus Edwards example, I re-made the earlier table and calculated the altered win equity of each pick based on Dobbins’ and Edwards’ draft range prior to and after the injury. To do so, I calculated the effect on win equity from the lost value points of a late third round pick, and the increased expected value of a late tenth converting to a late fifth.

Note: this table does not ‘re-balance’ the lost value among all 12 teams leading to a net negative win equity

The initial takeaway is unclear. The net shift in win equity is even between both “cuffing” and “non-cuffing.” However, in the remainder of this article, I will dictate why losing the only net benefit from your range of outcomes is so debilitating, and why there are unaccounted for variables that hurt the ‘cuffed’ win equity more than demonstrated above.

II. The Structure of Fantasy Football Leagues Rewards Ceiling More Than Floor

This argument is reminiscent of the one I made in favour of ceiling chasing in best ball tournaments. While this necessity is lessened in 12 person redraft leagues, the concept ought not be abandoned.

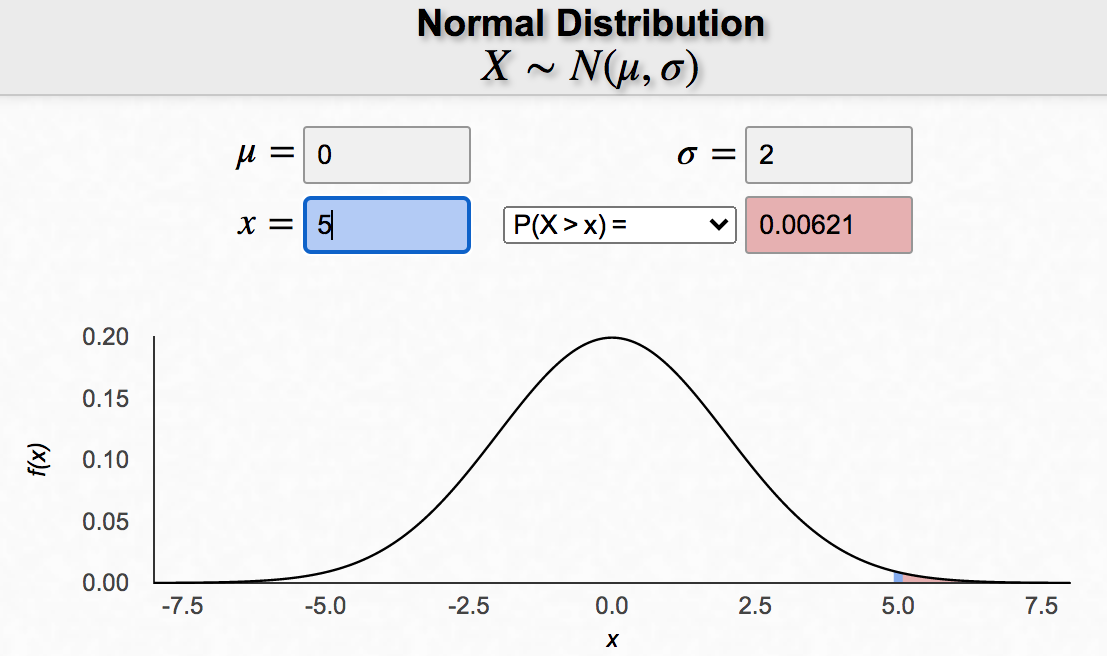

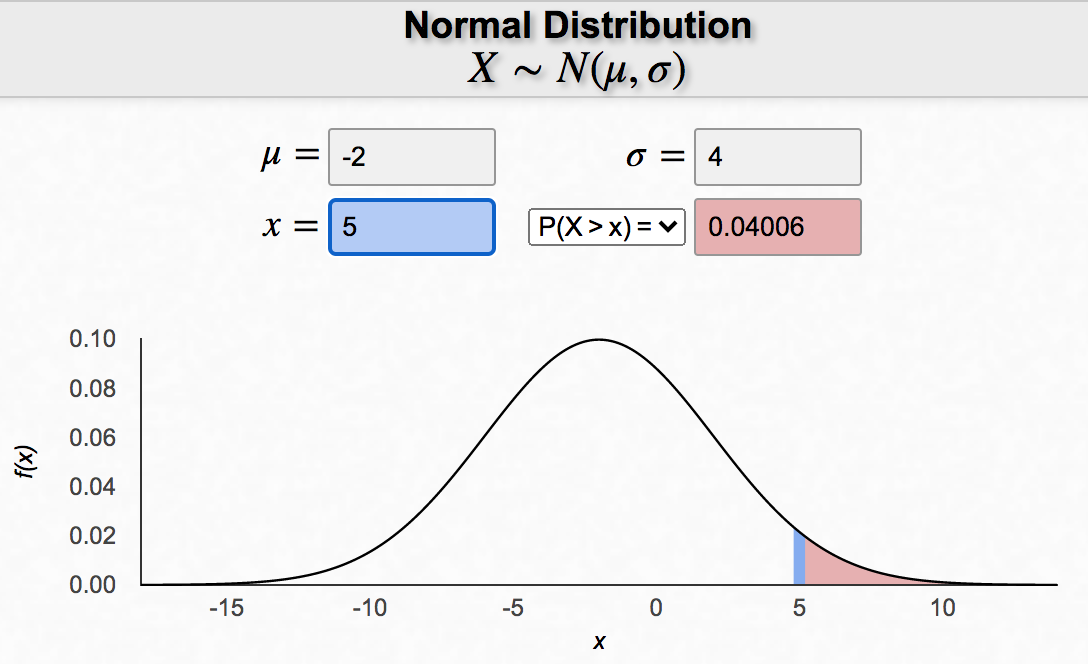

In that piece, I showed two normal distribution curves; one with a lower average and wider spread vs. a narrower curve with a higher average. The curve with higher variance was more likely to reach greater values on the tails of its distribution even with a lower average. To win a 12-person fantasy league requires a 92nd-percentile outcome (11/12 * 100). Taking a handcuff ensures you cannot have two players who will contribute to that outcome. That’s a legitimate ceiling limiter when you only have 15-18 picks in most leagues.

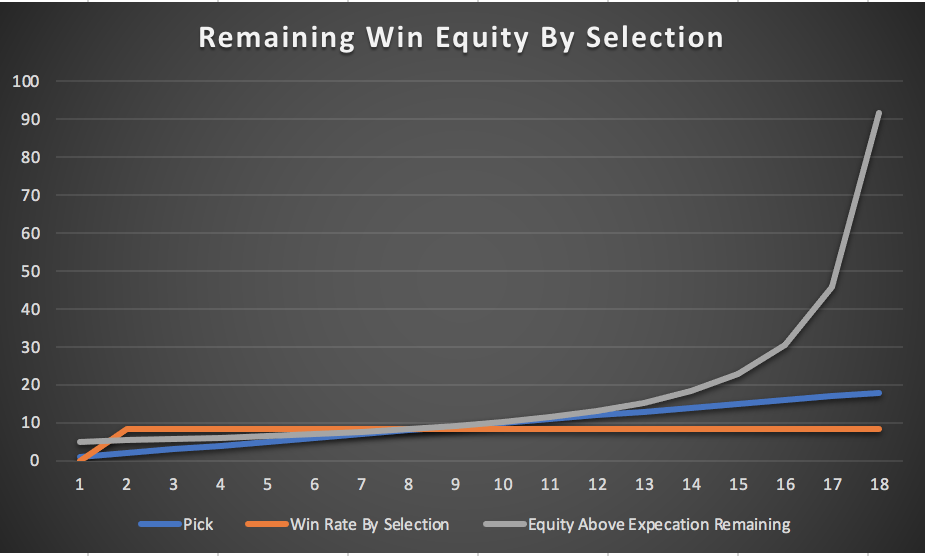

There is a misconception that 8.3-percent is the ‘neutral’ win rate for a player (one in twelve). But if each selection you make has an average win rate, your overall win equity will remain at 8.3-percent. The chart below shows the increase in necessary win equity as a result of each subsequent pick with an average win rate. Imagine you have a deadline on a project that requires 150 hours of work. If you only put in eight hours each day, you may be working a ‘neutral’ amount, but the work required in each subsequent day increases.

When the draft starts you only have an 8.3-percent chance to win! Handcuffing does not help you improve upon those odds, it merely protects against the loss of a floor that is precarious to begin with. Throwing away an opportunity to generate ceiling has a damaging knock on effect that puts additional pressure on each of the rest of your picks.

III. The Silent Cost of Handcuffing

Schrodinger’s cat is a thought experiment made famous in The Big Bang Theory in which a cat inside a box may be thought of as both alive and dead because its fate is linked to an event we cannot know the outcome of. That is the same way we should approach the contingent value of complimentary running backs. Running backs, especially in the double digit rounds, are not drafted according to projection. Each back’s ADP is a composite of their expected standalone value, and their contingent value.

For instance, if we knew Dalvin Cook would play 17 games, Alexander Mattison would not even be drafted. However, fantasy gamers have decided at a certain point, the upside of Mattison if Cook were injured is enough to justify the loss in standalone value. It is highly unlikely Mattison’s correct price looking back on this season is his current ADP. However the ‘cat’ (Cook) can at this moment be thought of as both alive and dead, and Mattison’s price is a composite of each.

Now let’s turn to the win equity chart from earlier, with an eye towards the ‘neutral’ boxes. If you roster a starter and handcuff and the starter remains healthy and effective, the handcuff has their contingent value robbed from their pre-draft outlook and will cause a downturn in win equity. Assuming you never start the player, it’s a 2.9-percent decrease according to the value chart. Your best case scenario is a small loss, and your worst case scenario mildly mitigating a larger loss.

This is why you should not allocate resources on a player who can only succeed if your larger investment fails. Either way, you lose.

The cost is likely even higher. Unlike best ball where your chances to generate win expectancy expire after the draft, handcuffing in redraft has further costs. Early weeks on the waiver wire offer the highest asymmetrical upside to pick up possible league winners for the low cost of a bench spot. However, you’re unlikely to ever drop your handcuff for a waiver claim after already making a sacrifice in the draft to secure your floor. This can cost you a potentially league-altering waiver claim, or force you to drop a higher upside player from your bench. The cost of devoting a bench spot to your handcuff extends far beyond the draft.

IV. Handcuff Running Backs Often Fail To Hit Value

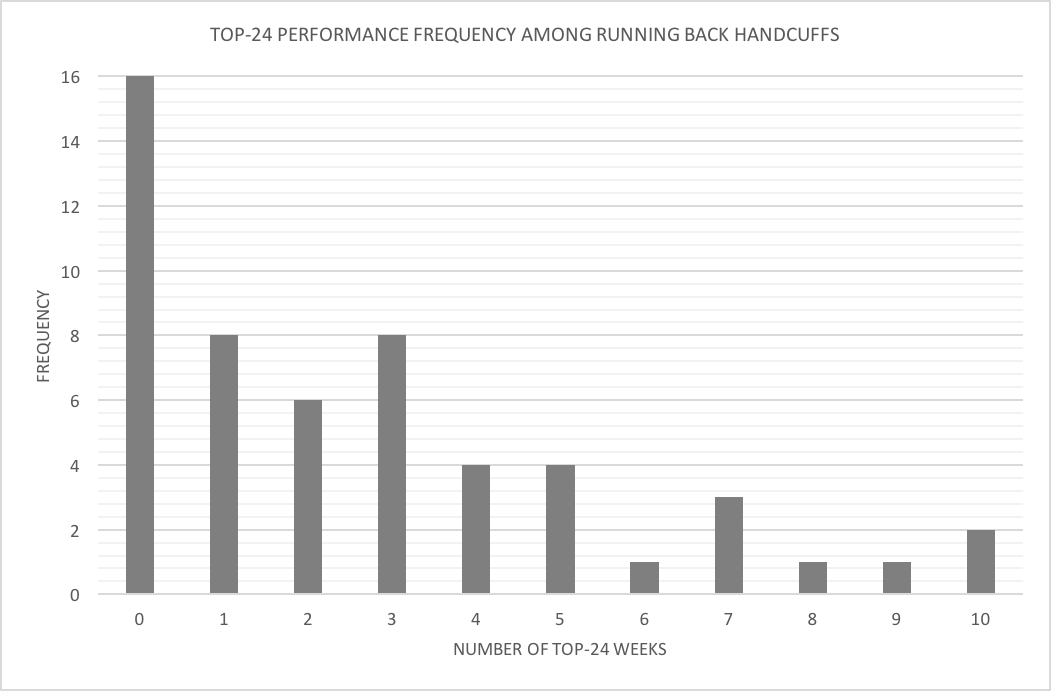

In a study by J.J. Zachariason, 54 running backs were drafted between Rounds 7 and 15 behind a top-12 running back from 2011-2017. Of those, 32 offered three or fewer top-24 finishes. This means a majority of the time you select a handcuff, you will have three or less useable weeks. That also includes games in which they score a random touchdown, or take over after a mid game injury when you would have left them on the bench.

Even more damaging, is the degree to which handcuffs fail when the starter goes down. Of 105 games the starter missed due to injury, rushers in this study hit top 24 status at just a 34-percent rate. To sum, drafting a handcuff is willingly sacrificing ceiling as we saw in section I, and is actually a worse play on average as we discussed in section III. But supposedly it’s all worth it for the peace of mind. However, even on the occasion you break glass in case of emergency, two thirds of the time there is no fire extinguisher to be found.

To put this all into one umbrella let’s examine the most successful handcuff case of 2020; Mike Davis.

Last year in 12 games he played without Christian McCaffrey, Davis registered 15.2 Fantasy Points Per Game. Many will use that as confirmation that handcuffing can solidify your floor after even the most debilitating injury. However, there are two big problems with this logic.

First, Davis was not even the clear handcuff drafted for McCaffery; Reggie Bonnafon was drafted ahead of him on most platforms. Second, Davis’ 15.2 points per game, while an incredible value off the waiver wire, would have been a decapitating result in Round 1, where McCaffrey was taken. Ezekiel Elliott, drafted a few spots behind McCaffrey, posted 14.9 points per game and had a 2.7-percent best ball win rate in 12 person leagues. Essentially, if you handcuff a Round 1 pick, and they produce 15 points per game after an injury, your win equity could still be cut by nearly 70-percent.

Conclusion: Handcuffing Learns the Wrong Lessons From Anti-Fragility

Anti-fragile is a term given by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who defines anti-fragile assets as those which benefit from disorder. Ben Gretch wrote an incredible post applying the concept to fantasy drafting in the immediate wake of the Travis Etienne injury. To quote Taleb, “anti-fragility is beyond resilience and robustness. The resilient resists shock and stays the same; the anti-fragile gets better.” I want you to consider this passage in relation to the handcuff debate.

Handcuff proponents have the correct first instinct. Chaos will ensue over the course of an NFL season, and drafters must act accordingly. But drafting the handcuff is the resilient approach. An anti-fragile approach does not protect against chaos, it weaponizes it. After the Cam Akers injury, I wrote about how to draft handcuffs in general (not your own).

The best way to benefit from chaos is to place players reliant on unpredictable binary outcomes in positions that maximize the utility of their ceiling.

Taking Alexander Mattison on a team with Ezekiel Elliott allows you the chance to stack hoards of receivers and an elite tight end, with the possibility of starting both Mattison and Elliott should Dalvin Cook get injured. That’s a team others cannot replicate or compete with. Drafting a handcuff to your own running back takes the possibility to benefit from chaos off the table. You can derive only benefit at your own expense.

Darrell Henderson and the Power of Assumptions in Best Ball

✍️ @FF_RTDBhttps://t.co/q5AltxtcXO pic.twitter.com/iwP9uL83mu

— RotoUnderworld (@rotounderworld) July 23, 2021

Albert Einstein once said “in the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity.” Injuries are the most devastating element of the game we love. But embracing this reality can set you up to make major leaps in win equity when injuries occur to others. You must never lose sight of the built in chaos of fantasy football. It is a game you will lose more often than not, but for that reason you must only play to win.